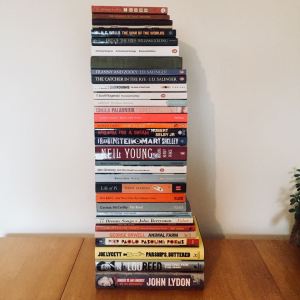

At the beginning of 2017, I set out to read fifty two books. Due to ill health, I didn’t quite make the whole fifty two, but I did read thirty seven in total, which is vastly more than I’ve read in a long time.

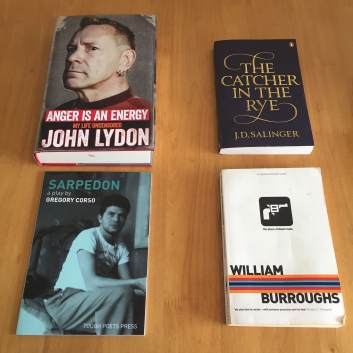

In reading so much I found some new favourites: J.D Salinger, Cormac McCarthy, Hubert Selby, Jr, Rupert Brooke, and Michael Horovitz, to name a few. I read some books by writers I already enjoyed: Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and James Franco. I also learnt a lot, whether that was about interesting personalities in the biographies and autobiographies I read, about the craft of writing, or just in soaking up the knowledge that these stories, poems, and one play offered.

I’m not sure I would try and read a book a week like this again. Not because I didn’t enjoy it while it lasted, but because for me personally, I found it took over and I lost time to do other things, like work on my own writing. Plus, although I read a lot generally, I’m not the fastest reader, so it may have been more time consuming for me than others to ensure I completed a book a week.

Over the course of twelve months, I read eighteen novels, one book of short fiction, six books of non fiction, eleven books of poetry, and one play. Here’s what I read, starting with a list of the novels in order of enjoyment.

Novels

1. ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ by Ken Kesey

It’s one of my favourite films, and I feel like I’ve let Kesey down a bit by not reading his novel first. A book that never lets up.

2. ‘Catcher in the Rye’ by J.D. Salinger

Concerned more with conveying a feeling than being heavy on plot. I’m not sure why it’s taken me so long to read this. I love Salinger’s understated style.

3. ‘The Road’ by Cormac McCarthy

Beautifully stark and brutal, like a post-apocalyptic Hemmingway novel.

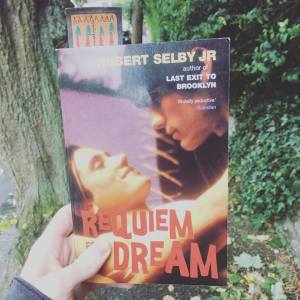

4. ‘Requiem for a Dream’ by Hubert Selby, Jr

An intense and desperate bullet train of a novel.

5. ‘Fight Club’ by Chuck Palahniuk

A unique story told with cut throat minimalism.

6. ‘The Great Gatsby’ by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Decadence that becomes harder to put down the further it builds up to the tragic nature of excess.

7. ‘A Clockwork Orange’ by Anthony Burgess

A twisted fable of good and evil, with plenty of ultra-violence thrown in.

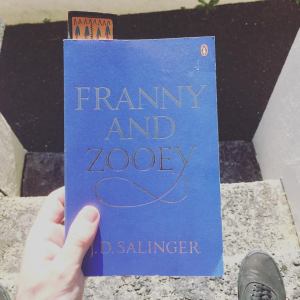

8. ‘Franny and Zooey’ – J.D. Salinger

A novel about depression comprised of a short story and a novella.

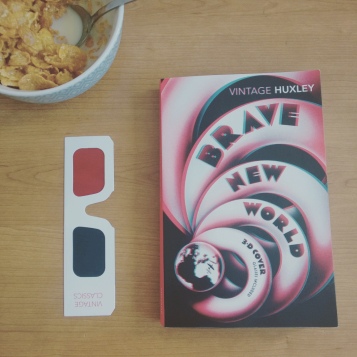

9. ‘Brave New World’ – Aldous Huxley

As relevant to our world today, controlled by media, celebrity, and sex, as it was in 1932.

10. ‘Life of Pi’ – Yann Martel

A page turner of fantasy and flight, which would be higher in my list if it wasn’t for those pesky anti-climaxes.

11. ‘Animal Farm’ – George Orwell

A fun read, and a clever introduction to the goings-on of the Russian Revolution.

12. ‘Lord of the Flies’ – William Golding

A war of egos, worth reading more for the plot than the clunky writing style it’s written in.

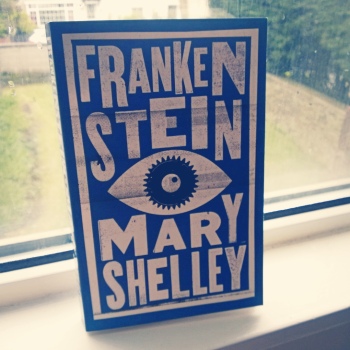

13. ‘Frankenstein’ – Mary Shelley

Well worth reading to realise the actual story of Frankenstein’s monster.

14. ‘Cry, The Beloved Country’ – Alan Paton (not pictured above)

An eye-opening book about the social, economic, and political conditions of 1940’s South Africa.

15. ‘The Place of Dead Roads’ – William Burroughs

The dreamlike imagery is amazing, but cut-up technique aside, this books feels really in-cohesive, and as a Burroughs fan, I hoped it would be better.

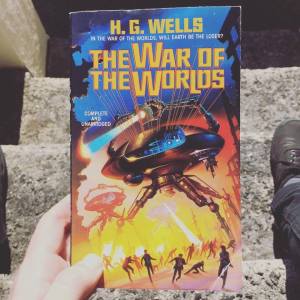

16. ‘The War of the Worlds’ – H.G. Wells

I’m not really sure what happened in this book. At least I can say I’ve read it.

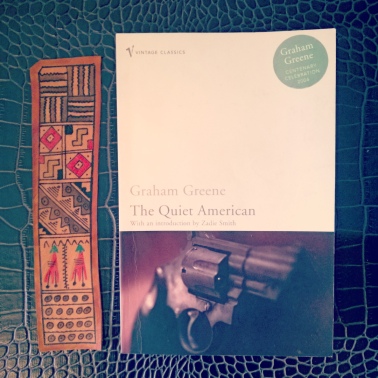

17. ‘The Quiet American’ – Graham Greene

Everybody seems to love this book, but I found it a pain in the rear to read. Oh, how bored I was.

18. ‘Money’ – Martin Amis

Some of this book was clever, and even enjoyable. But for the most part it was filled with so much unjustified misogyny, that the more I reflect on it, the more I can’t stand it.

Short Fiction

‘Over to You’ – Roald Dahl

Poetry (in no particular order)

‘Selected Poems’ – Rupert Browne

‘Love Opens the Hands’ – Bill Wolak

‘Burn Site in Bloom’ – Jamie Houghton (Buy it here)

‘Poems’ – Pier Paulo Pasolini

‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’ – Edward Fitzgerald

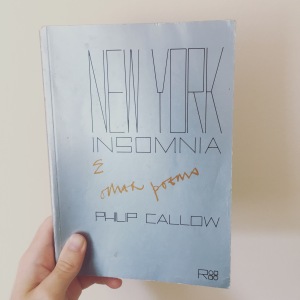

‘New York Insomnia’ – Philip Callow

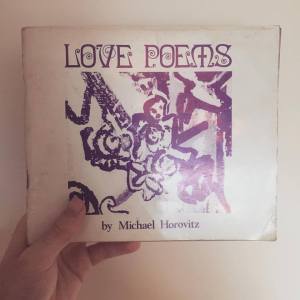

‘Love Poems’ – Michael Horowitz

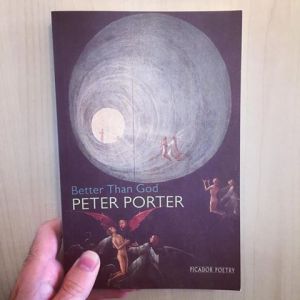

‘Better Than God’ – Peter Porter

‘Wait Til I’m Dead, Poems Uncollected’ – Allen Ginsberg

‘Straight James/Gay James’ – James Franco

’77 Dream Songs’ – John Berryman

Non Fiction (in no particular order)

‘Waging Heavy Peace’ – Neil Young

‘Anger is an Energy’ – John Lydon

‘Waiting for the Man’ – Jeremy Reed

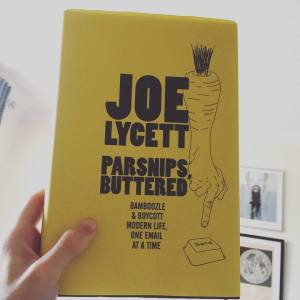

‘Parsnips, Buttered’ – Joe Lycett

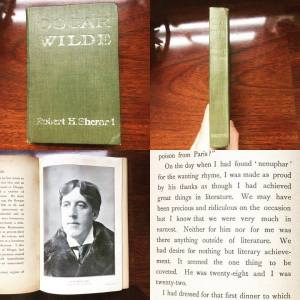

‘Oscar Wilde, The Story of An Unhappy Friendship’ – Robert H. Sherard

‘The Cube’ – Annie Gotlieb

Plays

‘Sarpedon’ – Gregory Corso

You can read my more in-depth thoughts on most of these books by scrolling down through my blog.

If you’re looking for something to read yourself, and fancy some poetry about being a father, please click here and reward yourself with that which you desire. Read a sample poem here. You can also read an article I wrote about my book on The Huffington Post.